Normal

0

MicrosoftInternetExplorer4

/* Style Definitions */

table.MsoNormalTable

{mso-style-name:“Table Normal”;

mso-tstyle-rowband-size:0;

mso-tstyle-colband-size:0;

mso-style-noshow:yes;

mso-style-parent:“”;

mso-padding-alt:0cm 5.4pt 0cm 5.4pt;

mso-para-margin:0cm;

mso-para-margin-bottom:.0001pt;

mso-pagination:widow-orphan;

font-size:10.0pt;

font-family:“Times New Roman”;}

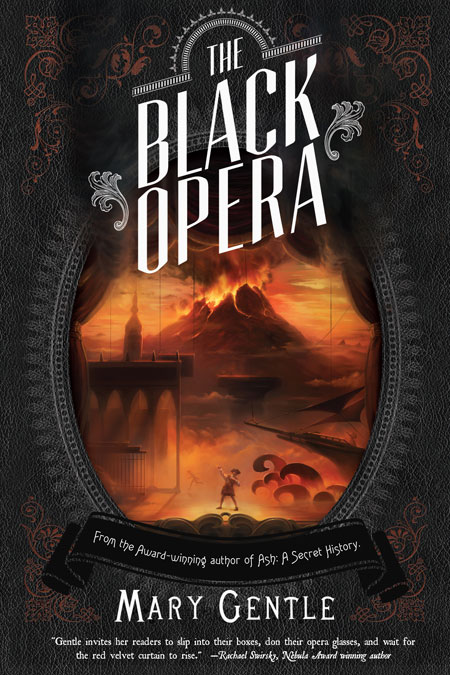

Mary Gentle is one of the authors who, though I didn’t realise it at the time, had a formative influence on me as a reader. She has a new novel out this summer, The Black Opera: a novel of operas, volcanoes, and the Mind of God, a magnetic story set in the 19th century Kingdom of the Two Sicilies—an alt-historical Two Sicilies with fantastic elements—and revolving around magical opera.*

*It’s really good.

In celebration of the fact, I’m going to spend some time spilling a few hundred words on Gentle’s career to date. Because she writes rather amazing stuff. And because her books are full of women doing both hard jobs and cool shit.

[Would I lie to you? No, wait, don’t answer that…]

I must have been fourteen when I pulled Ash: A Secret History**—all eleven hundred pages of it—off a bookshop shelf, seduced by the shiny lion’s head on the cover, the promise of a book that I couldn’t finish in a single day, and above all the sheer brilliant glittering conceit of a novel presented as a historian’s scholarly mystery, with footnotes and correspondence framing a brutally compelling journey across Europe, told with a visceral, convincing immediacy in precise yet evocative prose.

**There’s another long novel set in the same history, Ilario: The Lion’s Eye (Gollancz, 2006) that, while still a good read, is slightly less cohesive as a story and successful in its ambitions. Its main character, the titular Ilario, is an artist and a hermaphrodite—but if Ilario is less successful than Ash, it’s still inventively interesting.

Ash isn’t a squeamish book. It opens with rape and death, and continues to look unflinchingly at medieval life and medieval war. It’s gritty and epic and endlessly inventive, and though I’ve read it through more than once in the last decade, there are still parts that make me flinch. But it’s also a very human book: Gentle’s empathy for her characters, even the most twisted, is clear on every page. Their suffering is real and so are their flaws, but so too are their moments of grace.

And it’s full of cool shit. The past is another country, they do things differently there—especially in alternate history. Gentle’s worldbuilding is top notch, subtly cueing you in to the idea that Ash‘s fifteenth-century Europe is not ours. Little things, like references to the Green Christ; larger things, like the Visigoths and the Penitence over North Africa, weird fantastically cool things like Stone Golem and the Wild Machines —

But that’s not what—or at least, not all of what—let Ash: A Secret History have such a strong impact on me. Nor is it Gentle’s precise language and evident historian’s delight in every detail of medieval warfare and the realities of power. No. It’s the fact that this medieval Europe is full of women. Laundresses. Whores. Mercenaries. Cross-dressing lesbian battlefield surgeons who end up inheriting duchies.

When I was fourteen, I didn’t know how unusual this was. Ash is surrounded not just by all kinds of men, but by women of all sorts. The three most striking presences in the book—Ash herself, the Faris, who captains the Visigoth troops, and Duchess Floria of Burgundy, formerly known as the surgeon Florian—are all women. None of them are flat, or one-dimensional. Their weaknesses are balanced by their strengths.

Of course, Gentle isn’t best known for her most recent work. Her most well-known books are also some of her earliest: 1983’s science fictional Golden Witchbreed, a planetary romance with a complicated relationship to (post-) colonialism, and its more contentious sequel, 1987’s Ancient Light. Back in 2010, Niall Harrison wrote with insight and appreciation about Golden Witchbreed and—in conjunction with Duncan Lawie—about Ancient Light at Torque Control. Harrison articulates many of my impressions of both Witchbreed and Ancient Light with considerable acuity. Both are, in their own ways, accomplished works. They both examine similar themes from different perspectives, and succeed both as individual books and as a pair. But where Golden Witchbreed holds out the possibility of happy endings, Ancient Light is a novel shadowed by the inexorability of its ending. I enjoy Golden Witchbreed—but Ancient Light I admire and hate all in the same moment. Ancient Light doesn’t flinch from disillusionment: it inverts many of SF’s usual, hopeful expectations about the miracles of technology and progress. It makes for a good book, but an uncomfortable one.

Of course, Gentle isn’t best known for her most recent work. Her most well-known books are also some of her earliest: 1983’s science fictional Golden Witchbreed, a planetary romance with a complicated relationship to (post-) colonialism, and its more contentious sequel, 1987’s Ancient Light. Back in 2010, Niall Harrison wrote with insight and appreciation about Golden Witchbreed and—in conjunction with Duncan Lawie—about Ancient Light at Torque Control. Harrison articulates many of my impressions of both Witchbreed and Ancient Light with considerable acuity. Both are, in their own ways, accomplished works. They both examine similar themes from different perspectives, and succeed both as individual books and as a pair. But where Golden Witchbreed holds out the possibility of happy endings, Ancient Light is a novel shadowed by the inexorability of its ending. I enjoy Golden Witchbreed—but Ancient Light I admire and hate all in the same moment. Ancient Light doesn’t flinch from disillusionment: it inverts many of SF’s usual, hopeful expectations about the miracles of technology and progress. It makes for a good book, but an uncomfortable one.

Uncomfortable is a good way to describe most of Gentle’s work, actually. I mean, in general I find it brilliant, weirdly inventive, and shot through with moments of humour and grace, but there’s no escaping the fact that I still don’t know quite how to react to—or what to think of—the rape in 1991’s The Architecture of Desire, or the deliberately problematised sexualities of 2003’s 1610: A Sundial in A Grave. That’s without even considering the rock-and-hard-place nature of many of her characters’ dilemmas.

Also uncomfortable—or at least disconcerting—is the way she plays with expectation, genre, and continuity, particularly in the White Crow novels (Rats and Gargoyles, 1990; The Architecture of Desire, 1991; and Left to His Own Devices, 1994, collected in 2003 with three short stories as White Crow). It may well be fair to say that Gentle was writing “New Weird” at least a decade before Miéville coined the phrase.

Rather than fail to do the White Crow novels justice here, I’m going to dedicate a future column (or two) to talking about how they bend the boundaries of genre and how they show female characters as a neutral default, and the role of Hermetic science in Gentle’s fiction. (This isn’t just because as I was writing this column I kept getting distracted by the books themselves, I promise. But you might be forgiven for assuming that’s a considerable part of it.) Because in a way they’re ideal examples of the recurring impression I have of Gentle’s work: that in her books, the science fictional is frequently treated in the tone of the fantastic, but the fantastical is as rigorously thought-out to its logical conclusion as the hardest of hard SF.

In the meantime, let me leave you with a link to a novelette from 1991: “The Road to Jerusalem.” I’m not sure whether it’s brilliant or bizarre, but it exhibits a few of the themes and stylistic elements that keep showing up in the rest of Gentle’s work.

Liz Bourke is not capable of balanced critical evaluation where most of Mary Gentle’s work is concerned. So let’s just leave it at WOO YAY.